Why does ‘Brett’ smell different in different wines?

What are the sensory thresholds for ‘Brett’?

Are we becoming better at detecting ‘Brett’ or am I just super-sensitive?

Can ‘Brett’ affect white wines?

Are certain types of wines more likely to be affected by ‘Brett’?

Are there different strains of ‘Brett’?

What is the best way to monitor or measure ‘Brett’?

If my wines have ‘Brett’, how do I treat it?

Who should I contact if I need help with a ‘Brett’ problem?

Information pack on ‘Brett’– order resources online

What is ‘Brett’?

Brettanomyces (‘Brett’) is a type of yeast commonly found in wineries, which has the potential to cause significant spoilage in wines, through the production of volatile phenol compounds. These compounds (in particular 4-ethylphenol [4-EP], 4-ethylguaiacol [4-EG] and 4-ethylcatechol [4-EC]) are associated with undesirable sensory characters such as ‘Band-Aid’, ‘medicinal’, ‘horsey’, and ‘barnyard’ – collectively often referred to as ‘Brett’ character. Because Brettanomyces yeast are found across all Australian wine regions, and can cause such negative sensory effects, it is sensible for all wineries to have a control strategy in place, even if Brettanomyces spoilage problems have not been experienced in the past. Steps taken to control ‘Brett’ are also likely to have additional positive consequences in avoiding other microbiological spoilage, volatile acidity (VA) and general wine instability problems.

What does ‘Brett’ smell like?

4-EP, or ‘Band-Aid’ aroma, is the main contributor to ‘Brett’ character and is considered the general marker for Brettanomyces. Wine with ‘Brett’ presents with more than just a Band-Aid aroma, however, with 4-EG adding ‘smoky’ and ‘spicy’ notes, and 4-EC adding ‘savoury’, ‘sweaty/cheesy’ and ‘barnyard/animal’ nuances. The palate can also be affected; with diminished fruit flavour intensity and a drying/metallic aftertaste.

Why does ‘Brett’ smell different in different wines?

‘Brett’ compounds are usually always present together, albeit in different ratios. These ratios have been shown to be related to the different levels of their precursors naturally present in different grape varieties. Some typical ratios in varieties, and likely sensory effects compared to 4-EP alone, are shown below.

| Variety | 4-EP:4-EG ratio | Likely sensory effect |

| Pinot Noir | 3:1 | More leather and barnyard, spicy |

| Cabernet Sauvignon, Nebbiolo | 9:1 | Similar to 4-EP alone, but with a pungent spice |

| Shiraz | 23:1 | Similar to 4-EP alone, pure Band-Aid |

Thus while a ‘Brett’-affected Shiraz might smell like pure Band-Aid, a ‘Brett’-affected Pinot Noir will possibly smell more ‘animal’, ‘barnyard’ and ‘spicy’, perhaps akin to and often confused with savoury characters of Pinot Noir wines and heavily toasted or spicy oak flavours.

What are the sensory thresholds for ‘Brett’?

In a French Cabernet, Chatonnet and colleagues (1992) reported that the sensory perception threshold for 4-EP was 605 µg/L. Studies at the AWRI found a lower threshold of 368 µg/L for Australian Cabernet Sauvignon wines.

Further work at the AWRI has shown that the threshold of 4-EP depends very much on the style and structure of the wine, with the intensity of other wine components able to mask ‘Brett’ character. For example, the 4-EP threshold in a ‘green’ Cabernet Sauvignon wine, and in a heavily oaked Cabernet Sauvignon wine, increased to 425 and 569 µg/L respectively. As a wine ages, primary fruit flavours generally reduce and this can also sometimes reveal ‘Brett’ characters that have earlier been masked by fruit characters.

| Aroma threshold (µg/L)1 | |||

| 4-EP | 4-EG | 4-EC | |

| French Bordeaux Cabernet Sauvignon2 | 605 | 110 | – |

| Australian Cabernet Sauvignon3 | 368 | 158 | 774 |

| Australian ‘green’ Cabernet Sauvignon | 425 | 209 | 1131 |

| Australian ‘oaky’ Cabernet Sauvignon | 569 | 373 | 1528 |

1. ASTM three-alternative forced choice method, ascending concentration series

2. Chatonnet et al. 1992

3. Bramley et al 2007

More information about sensory thresholds can be found here

Are we becoming better at detecting ‘Brett’ or am I just super-sensitive?

Wines affected by ‘Brett’ usually contain both 4-EP and 4-EG. When present together there is an enhanced effect, and a lowering of the threshold. This was reported by Chatonnet and colleagues in 1992. Originally reporting the 4-EP threshold alone as 605 µg/L, this reduced to 369 µg/L when present with 37 µg/L of 4-EG (9:1 ratio). AWRI studies have shown the 4-EP threshold alone as 368 µg/L. but when combined with 4-EG the threshold is much lower than this. So if you are smelling ‘Brett’ in wines and having them analysed at levels below 200 µg/L then you might not be super-sensitive, it might be just the real threshold for the combined Brett compounds in that wine style. In addition, as with many aroma compounds, there is a learning effect and with repeated exposure to the aroma of ‘Brett’, it will be detected more easily.

In consumer testing, levels of 4-EP of 600 µg/L with 4-EG of 200 µg/L were sufficient to strongly reduce consumer preference, even though consumers would most likely not have been able to describe the flavour and in fact only 4% of consumers had heard of ‘Brett’.

Misdiagnoses of ‘Brett’

The AWRI helpdesk quite often receives wine samples suspected of being affected by Brett, yet a quick smell, and analysis if needed, reveals the wine to be ‘Brett’-free. It seems that ‘Brett’ is sometimes being blamed for other wine faults – including sulfidic characters (‘sewerage’, ‘sweaty’, ‘rotting onions’), low levels of oxidation that reduce fruit intensity and add a ‘savoury’ note and smoke taint. It is important to know what 4-EP and 4-EG smell like for your own sensory memory bank and to be able to identify Brett problems in the winery. Wine aroma kits are available for purchase, or you could attend one of the AWRI’s tastings.

Do some people like ‘Brett’?

The AWRI conducted consumer studies to determine if some segments of the population ‘liked’ the ‘Brett’ character in wine (Curtin et al. 2008). A group of 104 Sydney-based red wine consumers assessed a number of wines both unadulterated and spiked with Brett spoilage compounds, at a range of different concentrations. The unadulterated base wine was always most strongly liked. Samples with high ‘Brett’ spikes with 3:1 ratio of 4-EP:4-EG were least liked. All samples containing ‘Brett’ compounds were significantly disliked (p<0.05) compared to the base wines, indicating that a high proportion of individuals in the study did not like ‘Brett’ character.

Strong negative correlations of liking scores with ‘medicinal’ aroma, and ‘medicinal/leather’ flavour were observed; that is, the higher the level of ‘Brett’ flavour, the lower the score for consumer liking. It was remarkable that even the lowest level of ‘Brett’ flavour, with 4-ethylphenol at 600 μg/L, substantially affected consumer acceptance. This highlights consumer sensitivity to ‘Brett’ character. Interestingly, only 4% of panellists indicated that they had heard of ‘Brett’ and/or Brettanomyces in an exit questionnaire.

Do all wines have ‘Brett’?

At one time it was commonly thought that all red wine has ‘Brett’, just in different amounts. In the late 1990s this was probably the case. At the completion of the AWRI’s 10-year ‘Brett’ survey of Cabernet Sauvignon wines, the mean level of 4-EP in Australian Cabernet Sauvignon had dropped by a dramatic 90%, with a mean 4-EP of 107 µg/L reported for the 2005 vintage, and 21% of all wines measured from the 2006 vintage having ‘not detectable’ levels of 4-EP or 4-EG.

Can ‘Brett’ affect white wines?

Yes. 4-EP and 4-EG, the two main compounds associated with ‘Brett’, originate from two hydroxycinnamic acid precursors: p-coumaric and ferulic acids. These acids are found in both red and white grapes. So, given the precursor compounds for 4-EP and 4-EG are present in white wines, there is potential for 4-EP and 4-EG to be generated if ‘Brett’ grows in a white wine. Chardonnay is the white variety most frequently affected by ‘Brett’ characters. ‘Brett’ has also occasionally been observed in Riesling and in sparkling base wines.

White wines are more at risk of ‘Brett’ spoilage if left exposed to oxygen or with minimal SO2 handling. ‘Natural’ winemaking, where there is limited or no use of SO2 at the crusher and during ageing, increases the likelihood of ‘Brett’ growth and also other microorganisms. Storage on yeast lees such as for barrel-fermented Chardonnay wines or using skin contact time to achieve texture may extract more volatile phenol precursor compounds and malolactic fermentation leaves wines susceptible to ‘Brett’ growth while SO2 levels are low.

Are certain types of wines more likely to be affected by ‘Brett’?

‘Brett’ only needs 0.3 g/L sugar to produce 1000 µg/L 4-EP (Coulter 2010). The average glucose+fructose levels in Australian red wines had increased to 2.1 g/L (Godden et al. 2010) in 2008, from 0.5 g/L in 1998. Increasing alcohol levels over time, stuck or sluggish ferments, or consumer-driven sweetness levels in reds, does mean there are more red wines with some residual sugar which are therefore at risk and might require filtration when previously they did not. Unneeded or excessive use of yeast nutrient and nitrogen during fermentation can leave residual nitrogen as a food source and might under some circumstances increase ‘Brett’ risk, as well as increase the risk of growth of other spoilage organisms.

The ‘Brett zone’ is now known to be the critical time between the end of primary and secondary fermentation until the point before sulfur dioxide (SO2) is added. Leaving wines unsulfured for long periods of time, particularly during slow malolactic ferments (MLF), is the riskiest time for ‘Brett’ growth. Ideally, MLF should be finished quickly. A molecular SO2 concentration of 0.6 mg/L is required to prevent Brettanomyces growth, and is best achieved by one large addition of SO2 post-malolactic fermentation, rather than a number of smaller additions. An addition of approximately 80 mg/L is generally recommended for wines of pH 3.6 or below. Higher pH wines need greater SO2 additions to reach 0.6 mg/L molecular SO2. The AWRI provides an easy way to calculate molecular SO2 via its online calculator or wine calculator app.

Are there different strains of ‘Brett’?

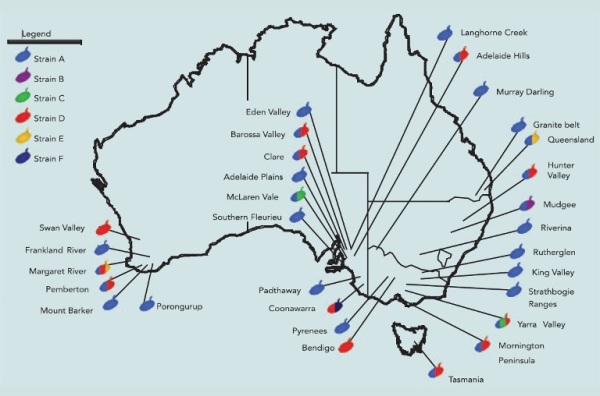

As part of the AWRI’s ‘Brett’ research (Curtin et al. 2005), Brettanomyces strains were isolated from approximately 50% of the winemaking regions across the country. Six genetically distinct strains were identified; however 85% of the isolates were related to one strain, known as Strain A. Some wineries harboured one strain, but others contained up to three strains. Strain A does appear to be highly adapted to the wine environment and has some tolerance to SO2.

Distribution of strains of Brettanomyces yeast isolated from Australian winemaking regions, 2002-2005

What is the best way to monitor or measure ‘Brett’?

Wines can be routinely measured for 4-EP; however, this is expensive and only alerts you once there is already a problem. A range of ‘Brett’ sniff test kits are also available where wine is added to broths, and if the wine contains ‘Brett’ yeast they will grow and produce 4-EP levels that can be readily detected sensorially. Routine microbiological testing is also costly and time consuming. An effective way of monitoring for ‘Brett’, and other microorganism growth during barrel ageing, is simply to measure the ratio of free to total SO2 ratio. If ‘Brett’ or other microorganisms are active, then the amount of free SO2 as a proportion of the total will drop. This is due to the growing microorganisms binding up free SO2. Ideal ratios of free to total SO2 in a finished wine are 1:2 or 1: 3 (e.g. 30:60 or 30:90). Once the ratio reaches to 1:5, it suggests something is binding up the SO2 and action needs to be taken. Now that AWRI researchers have sequenced the Brett genome (Curtin et al. 2012), future diagnostics tests are likely to become available including rapid PCR identification of yeast and tests to identify sulfite-resistant ‘Brett’ strains.

If my wines have ‘Brett’, how do I treat it?

When it comes to ‘Brett’, prevention is always better than cure. Routine sanitation will prevent population build-up in your winery. The key ways that ‘Brett’ is often spread around wineries include wine transfers, putting clean wine into contaminated barrels or vice versa, and cross contaminating barrels via topping, sampling or barrel stirring. Affected barrels should be treated by filling with hot water (ideally at 85°C for 15 minutes, or until the outside of the barrel is hot to touch). Treated barrels should then be marked and monitored carefully the next time they are used. Barrel disposal in some instances might be a safer option. Ozone and ultrasonics have also been reported as treatment options. Brettanomyces yeast cells can be removed from wine by sterile filtration, and can be kept under control with effective SO2 management. Reduction of 4-EP by reverse osmosis treatment is offered by several companies, or low levels of 4-EP can be blended away to levels below threshold.

How do I control ‘Brett’?

The growth of Brettanomyces is wine is affected by a range of factors, some of which are interlinked. This means that controlling ‘Brett’ requires a multi-faceted approach. The key factors to address are:

- General sanitation

- Residual sugar

- pH and SO2

- Barrel sanitation and topping

- Filtration and clarification

More detail can be found in the AWRI fact sheet Controlling Brettanomyces during winemaking fact sheet

Can ‘Brett’ grow in bottle?

Production of 4-EP in-bottle after packaging can occur in wines that contain viable Brettanomyces cells. There are two possible scenarios:

1. Each bottle has a different concentration of ‘Brett’

This scenario occurs when all bottles of the wine contained viable Brettanomyces cells after bottling. The variation in 4-EP levels is likely due to either variations in starting cell numbers in the bottles, variations in storage conditions, variations in the closure, or a combination of these factors.

2. Only some bottles show ‘Brett’ character, others are unaffected

This scenario can occur if a wine bottled without filtration contained very low viable cell numbers at the time of bottling. Some bottles could end up with at least one or more cells and others would not contain any. Alternatively, this scenario could arise through contamination of equipment at bottling, such as a portion of contaminated filler heads.

Who should I contact if I need help with a ‘Brett’ problem?

The AWRI’s winemaking helpdesk offers technical assistance to Australian grapegrowers and winemakers and can be reached on helpdesk@awri.com.au or 08 8313 6600.

Affinity Labs also offers a Brettanomyces audit service. For more information on this service, please contact Affinity Labs on customerservice@affinitylabs.com.au or 08 8313 0444.